Responses to COVID-19: South Africa vs UK

Although impacts have been severe, the pandemic has unfolded in unexpected ways globally. In this blog I compare responses to COVID-19, having experienced the pandemic in both the UK and Cape Town.

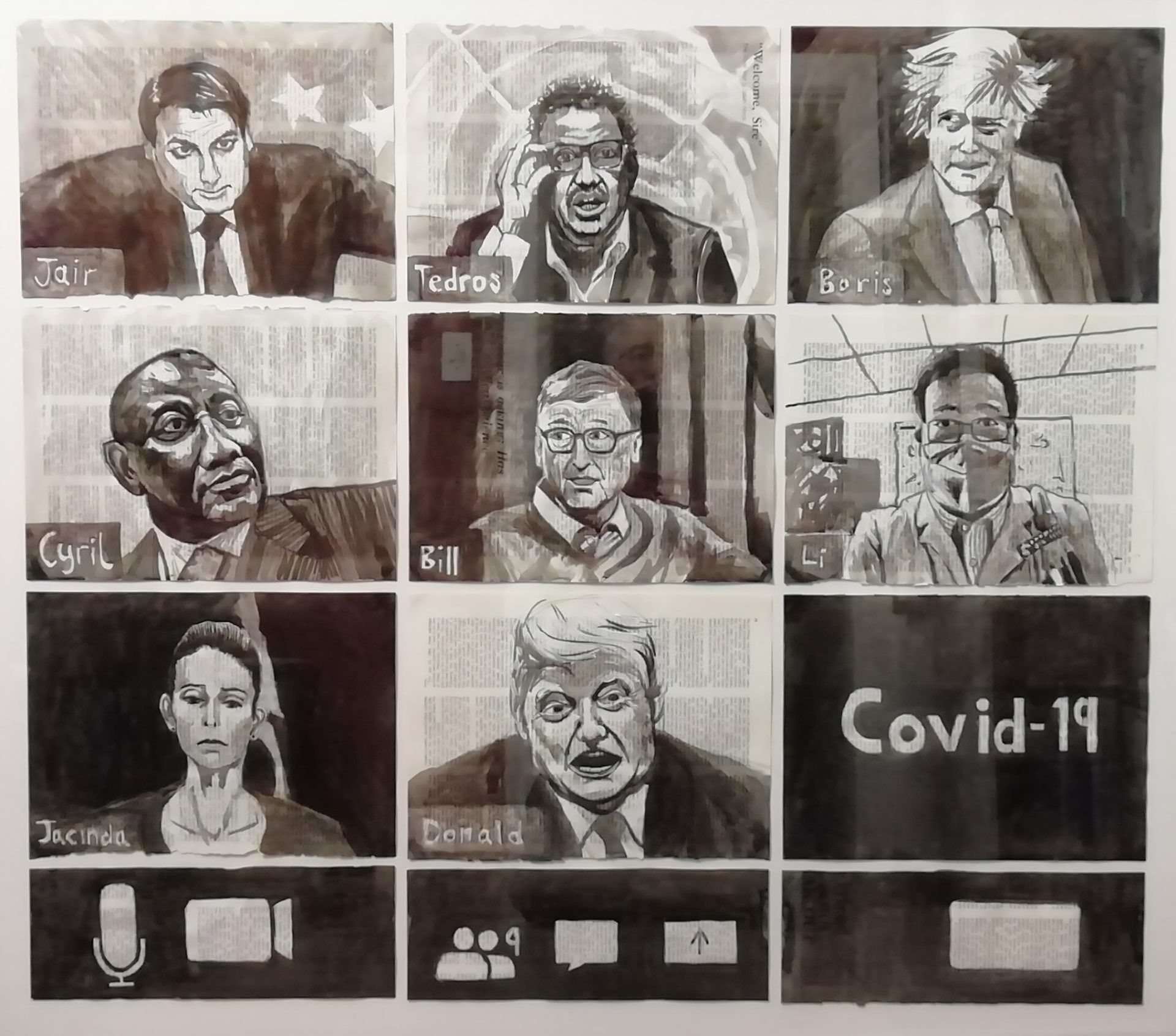

“COVID-19 has entered the room” by Bob Mash, 2020 (photo of artwork at the Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, February 2021)

Healthcare

South Africa’s initial policy response was one of the strictest lockdowns in the world. Alcohol and tobacco sales were banned and a 9pm curfew was imposed. Similar to the UK, restrictions were explained to the public as necessary to protect healthcare services from becoming overwhelmed. On new year’s day in 2021 photos from the third largest hospital in the world, in Soweto, went viral in South Africa.

Pictures posted on Twitter showing an empty trauma ward in Johannesburg

The pictures of an empty trauma unit were taken by hospital staff and posted on their Facebook page. It was evidence that restrictions had reduced hospital admissions, but also drew attention to the disturbing link between alcohol consumption and levels of violence in South Africa.

Later that month, similar scenes were posted on social media of seemingly empty UK hospitals. The BBC published an article explaining the footage, along with interviews with health staff, to show how the scenes misrepresented the reality. For example, filming was at night and in corridors not wards. The videos were part of anti-lockdown activism to undermine government claims that restrictions were needed to protect the NHS.

“Covid: The truth behind videos of 'empty' hospitals” (Screen grab from BBC News)

Freedom Day

Since March 2020, the relaxation of rules in South Africa has followed the same five stage approach. Similar to the UK, announcements are made about changes from one stage to another depending on rates of infection. I have not come across any widespread expectation that the relaxation of rules will remain in place permanently. The closest the UK has come to this kind of system was the four step roadmap announced in February 2021. The UK social media response was excitement about ‘freedom day’ in anticipation of the removal of all restrictions.

Nobel Square in Cape Town symbolises post-apartheid South Africa (Statues from left to right: Nkosi Albert Luthuli, Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, former State President FW de Klerk and former President Nelson Mandela)

In contrast, Freedom Day in South Africa is the annual public holiday to commemorate the first democratic elections held in South Africa on 27 April 1994. Therefore, freedom has a strong association with the end of Apartheid, as opposed to in the UK where COVID-19 rules have been framed as rights violations.

Vaccine apartheid

Currently, discussions about globalised power dynamics are focused on the fact that the UK is on its third round of vaccinations while the majority of the rest of the world have yet to be offered a first dose. Everyone I know in Cape Town who wants a vaccination has been able to access one. But similar to the UK, there has been vaccine hesitancy concerning the efficacy and safety of vaccines, which may partly explain the number of people getting vaccinated slowing despite South Africa having adequate supplies. Both UK and South Africa have used social media to encourage vaccine uptake, where both are addressing public mistrust of government.

“Going Viral” Micky Fritz, 2020 (photo of artwork at the Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, February 2021)

Policing

In March 2020, South Africa deployed troops to enforce the strict lockdown where only essential workers were allowed to leave their home. This attracted UK media attention concerning the unnecessary use of violence against people who had ventured outside. In contrast, during the UK’s first lockdown people were allowed outside for an hour a day to exercise. However, early findings from Co-POWeR’s research indicates that Black youth could not use their hour to go for a jog or cycle because of being stopped by the police. A participant in Wales told me that there were times where he could not get as far as the end of his street before being stopped and told to return home. Although exercising in South African townships is difficult, this is generally due to limitations on safe open spaces as opposed to racialised stop and search practices.

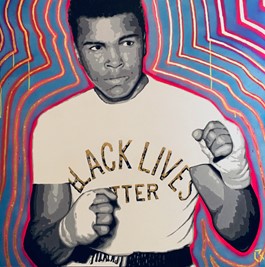

“Ali Power” by Alex Marmarellis, 2020 (photo of artwork at the Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, February 2021)

Has COVID-19 challenged the global North/South divide?

Back in March 2020, the UK media feared the worst for people in middle or lower income countries. South Africa was reported as an example of peoples’ inability to socially distance in townships composed of tightly packed informal housing structures.

Aerial view of the spatial patterns of informal housing in ‘townships’ near Cape Town’s flight path

But despite the UKs comparative advantage in terms of infrastructure, overall rates of infection and deaths have been much higher (although not evenly distributed across all populations). There are various theories that attempt to explain differences in the impact of COVID-19 in South Africa compared to countries in the global North. Among them is South Africa’s health response and experience of rapidly responding to infectious diseases. This is in stark contrast to the UK’s initial hesitancy around wearing masks, which has never stopped being mandatory in South Africa since the pandemic outbreak. This is not to suggest that South Africa has traversed the pandemic unscathed. There have been huge job losses and unlike the UK, there were no furlough schemes. International travel bans have hit the tourist industry and this has been keenly felt in Cape Town. All in all, despite historical disadvantages rooted in colonial era and apartheid legacies, expectations of how South Africa would fare in the face of a global health crisis have been turned on their head – especially when compared to the UK.

Blog post by Dr Teresa Perez