How school-based interventions support the well-being of Black youth

(Photo credit: Unsplash, NeONBRAND)

In response to a request from Ms Amoako-Williams, the Equalities Lead at Wilson’s School, Co-POWeR’s research will be used in planning a mental health symposium in London which will focus on supporting students from ethic minority backgrounds. I was asked to find out what school-based interventions have been successful, particularly in the context of UK schools with ethnic minority populations that are higher than the national average. This blog starts with a summary of a 2017 project in Birmingham and the connection between racism and emotional health. I then link its recommendations about safe spaces and positive images, to what young people in Co-POWeR’s study told us about best practice in schools since the pandemic. All quotes are from pages 5 – 6 of the Against All Odds report (available in full here).

(Photo credit: Unsplash, @linkedinsalesnavigator)

(Photo credit: Unsplash, @linkedinsalesnavigator)

Black Youth in Birmingham

Aged 11, Black people who identify as male do not have poorer mental health than others of their age. By the time they are adults, men from African Caribbean communities in the UK have far higher levels of diagnosed severe mental illness than other communities. This points to a deterioration in mental health during teenage and young adult years, which an intervention called ‘Up My Streets’ sought to understand.

(Photo credit: Unsplash, @santivedri)

(Photo credit: Unsplash, @santivedri)

Racism and mental health

Racism influenced mental health, which wore down young peoples’ resilience during their teenage years. For example, the incrementally “damaging impact of a constant stream of negative media representations of black men and demonising portrayals of black culture” led “young men to ‘mask’ their true selves”. The impact of the Up My Streets project supports recommendations emerging from Co-POWeR’s research with children, young people and families.

(Photo credit: Unsplash, @linkedinsalesnavigator)

(Photo credit: Unsplash, @linkedinsalesnavigator)

Safe spaces

Interventions need to provide “culturally and psychologically informed safe spaces encouraging aspiration, openness and positive relationships with other young black men”.

The availability of safe spaces in terms of school-based services, ranged from having a safe guarding leader to a counselling service. A 19 year old Black Caribbean participant who identified as male explained the difference he noticed in mental health support in his college in Leeds. He preferred spaces where he did not have to explain himself or feel bad about what he was saying, and where his economic difficulties were fully understood. This enabled him to be open about conflicts he was experiencing between cultural expectations and his sexual identity. Spaces to talk in school are less likely to be used if they are not experienced as safe, non-judgemental spaces, staffed by people who are empathetic.

Image caption: Mista Strange spoke about the impact homophobic Tweets on his mental health as part of ‘We Are Black and British’ BBC television series

(screen grab from episode 1, first aired on 23 Feb 2022)

Positive images of black culture

Interventions need to convey “a positive picture of black culture and heritage, countering dominant portrayals of the past and present”.

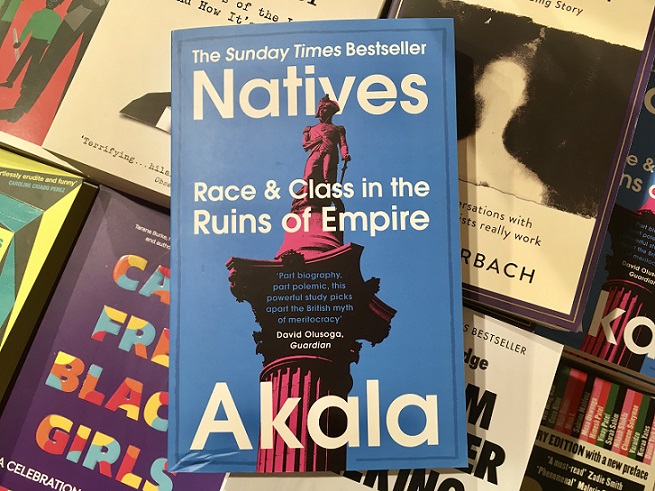

In Co-POWeR’s research, young people told us about their school’s approach to Black history. A 17 year old dual heritage participant who identified as female, appreciated the Black Lives Matter reading group at her school. Although primarily a book club, the sessions facilitated by her head of year are also to talk about politics and race relations throughout the school year. This compared to other young people who saw their schools’ annual presentations during Black History Month in tutor time/registration as somewhat superficial. Equally, adding one poem by a Black person to the reading list for GCSEs was seen as a gesture. Interventions therefore need to be ongoing rather than one off events that risk being interpreted as box ticking exercises.

Picture caption: At the time of being interviewed, the Black Lives Matter reading group were talking about Natives by Akala

Picture caption: At the time of being interviewed, the Black Lives Matter reading group were talking about Natives by Akala

A more detailed review of school-based interventions will be available on the Co-POWeR website ahead of the mental health symposium in May 2022. This is part of Co-POWeR’s review of literature about support for children, young people and families, which our work builds on, in preparation for our end of project report.

Blog post by Dr Teresa Perez